What is triple-A, and which countries make the grade?

Since voting to leave the EU, the UK has lost its prized AAA credit rating Image: REUTERS/Andrew Winning

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

United Kingdom

Among the headlines in the days that followed the United Kingdom's vote to leave the European Union, one was the fact that the country had lost its triple-A credit rating.

So what is a credit rating, and why does it matter?

In simple terms, a credit rating is the measure of how well an entity – whether that’s a country, company or individual – can pay back the money it has borrowed. In other words, its credit-worthiness. In the case of the UK, it’s a sovereign credit rating, meaning that it applies to the country as a whole. The sovereign rating is not just a measure of whether a country is good for the money, but of how it is faring politically, economically and financially.

All three of these factors have been affected by the Brexit vote, said the rating agency S&P after its decision to downgrade the UK’s sovereign credit rating:

“In our opinion, this outcome is a seminal event, and will lead to a less predictable, stable and effective policy framework in the UK. We have reassessed our view of the UK's institutional assessment and now no longer consider it a strength in our assessment of the rating.”

Who decides the rating?

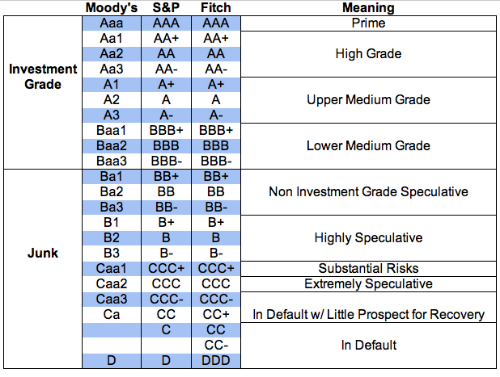

There are three main credit agencies: S&P, Moody’s and Fitch. Moody’s and Fitch had already downgraded the UK, from Aaa and AAA to Aa1 and AA+ respectively, in 2013 when the government announced further austerity measures.

Triple-A is the highest rating that can be given, and triple-D is the lowest. Anything below a B, however, is viewed as pretty risky. The ratings are broadly divided between "investment grade" and “junk”. The lower the rating, the greater the risk that the borrower will not be able to pay back the money.

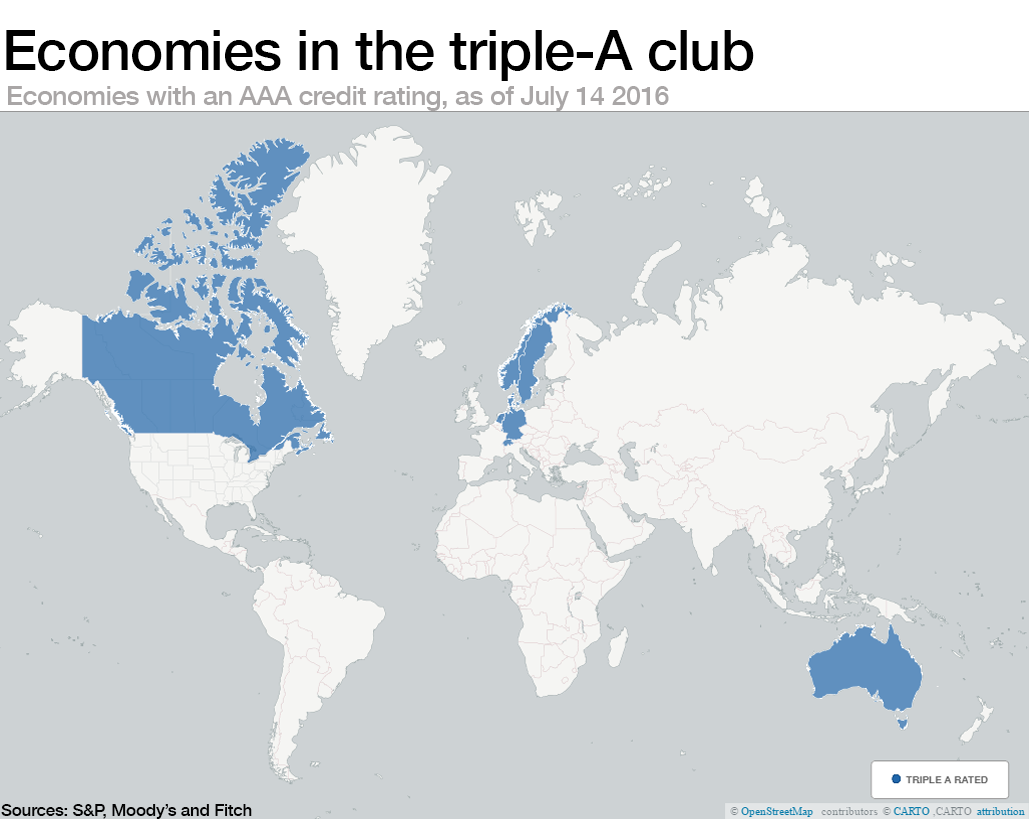

There are very few countries that belong to the AAA club. At the moment they are Australia, Canada, Denmark, Germany, Hong Kong, Liechtenstein, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, Sweden and Switzerland; and, until very recently, the UK. Hong Kong, which has Special Administrative Region status, has its own credit rating (AAA, from S&P).

Some countries are close to the mark. The United States, for instance, was downgraded by S&P in 2011, but retains its Aaa/AAA from the other agencies.

What do 'outlooks' mean?

There are also “outlooks” that accompany the credit ratings. So for example, while Australia has a triple-A rating from S&P, it is accompanied by a negative outlook, meaning that the agency is looking closely at a downgrade. The agency will always set out its reasons for doing so. In Australia’s case, it cites an unresolved federal election result and high levels of external and household debt in its assessment that there is a one in three chance that the country will be downgraded in the next three years.

The agencies produce solicited and unsolicited ratings. Solicited ratings are where the borrower has been involved in providing information to the agency and has paid for the rating, and unsolicited is where the ratings agency has used publicly available data to assess its ratings, and the borrower has not paid for the rating.

What’s the effect of the rating?

When a government seeks to borrow money, its rating reflects its ability to pay back the amount. The higher the rating, the cheaper the borrowing cost. This of course has a wider effect on the economy, as the government is pushed to tighten its belt to be able to afford higher borrowing costs.

When a rating agency assesses a country, it will look at financial statistics, or quantitative analysis, as well as a whole host of other factors including overall economic conditions, regulatory changes and political upheavals. According to S&P: “In rating a sovereign or national government, the analysis may concentrate on fiscal and economic performance, monetary stability and the effectiveness of the government’s institutions.”

In order to win back its triple-A rating, the UK would have to have stable economic growth, a stable government and no threats to its constitution. In the wake of the Brexit vote, it may be a long time before it can lay claim to having any of these.

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Financial and Monetary SystemsSee all

Kate Whiting

April 23, 2024

Joe Myers

April 19, 2024

Libby George

April 19, 2024

Valérie Urbain

April 19, 2024

Claude Dyer and Vidhi Bhatia

April 18, 2024

Efrem Garlando

April 16, 2024