A sixth mass extinction is underway - and it's our fault

Over the past 500 years, there have been four other mass extinctions on Earth, not including dinosaurs. Image: REUTERS/Mathieu Belanger

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Future of the Environment

The disappearance of the dinosaurs is probably the world’s most famous example of a mass extinction, but it’s certainly not the only one.

There have been at least four other mass extinctions on Earth over the past 500 million years.

A mass extinction refers to the die-off of a huge number of species in a relatively short period of time. In the past, mass extinctions have been caused by geological or climatic events, such as the asteroid strike that wiped out the dinosaurs.

But according to scientists, we are experiencing another mass extinction. And this time, it’s of our own making.

Biological armageddon

A new study published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences says that there is a “biological annihilation” underway.

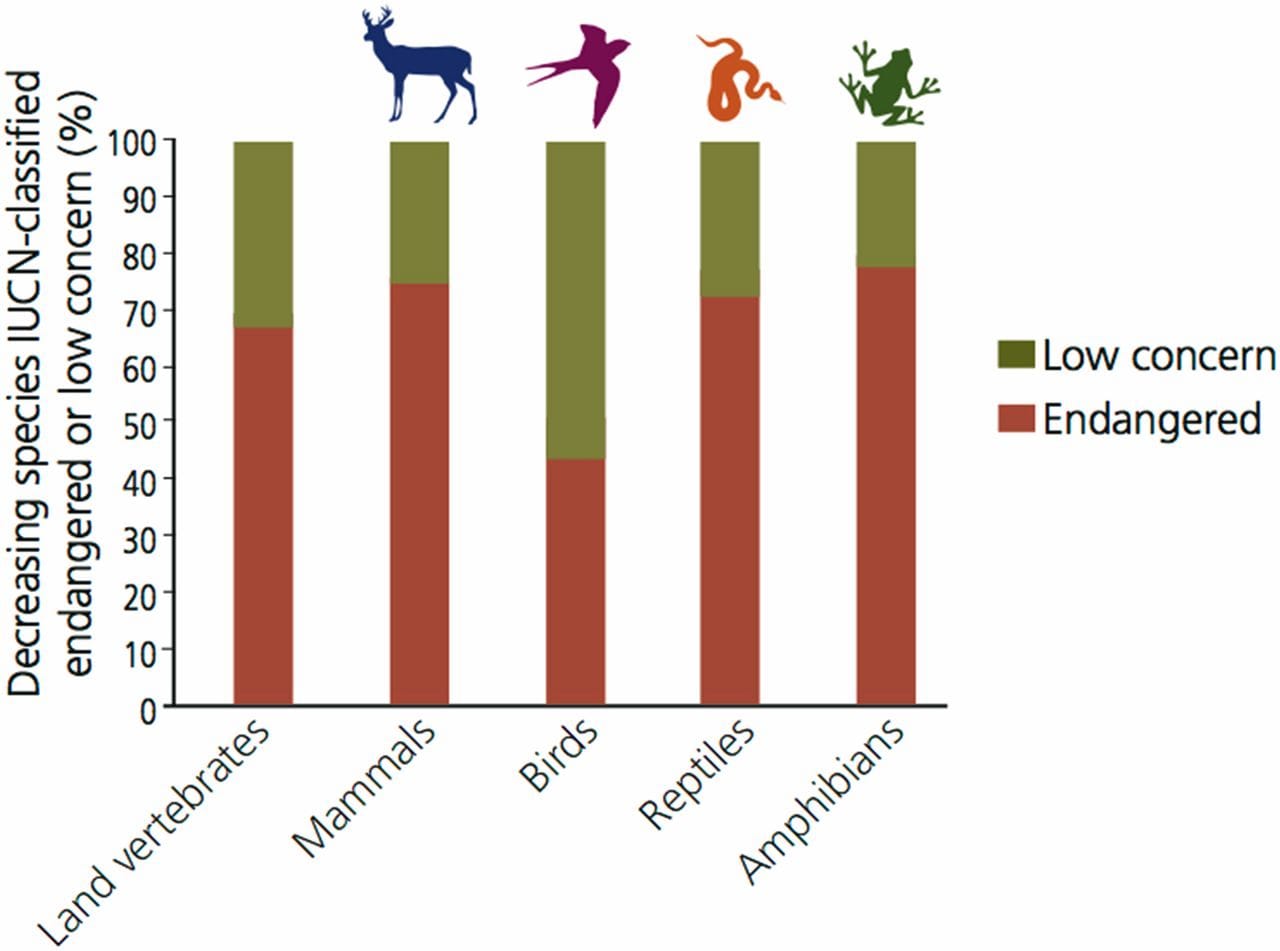

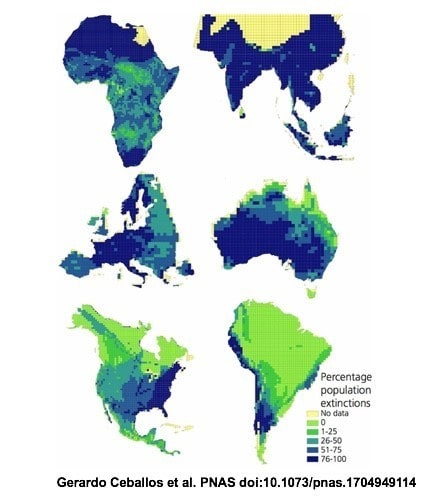

Researchers from Stanford University and the National Autonomous University of Mexico looked at 27,600 terrestrial vertebrate species (animals with a backbone that live on land), which represent around half of all vertebrate species, and found that 32% are decreasing in population.

They also looked at 177 mammal species, and found that all have lost at least a third of their geographic ranges. In addition, nearly one in two of the species have experienced severe population declines.

Several species of mammals that were relatively safe one or two decades ago are now endangered. For instance, the number of African lions has dropped by 43% since 1993.

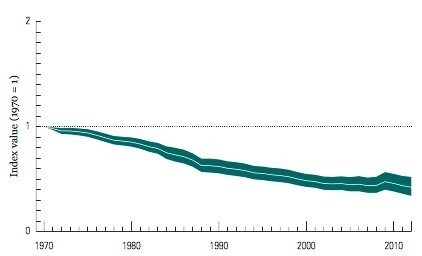

The study is not the only piece of research to come to the conclusion that certain species are declining rapidly. The Living Planet Index, which measures the number of 3706 vertebrate species, also shows a persistent downward trend.

This one is different

Although mass extinctions occurred before humans took over the planet, the scientists say that the rate of die-offs has speeded up considerably.

Even by their conservative estimates, almost 200 species of vertebrates have become extinct in the last 100 years. This is equivalent to around two species a year. In past extinctions, the loss of 200 species would have taken up to 10,000 years.

The problem, say the authors of the study, is that two extinctions a year do not attract enough global attention, especially if people have not heard of the creature in the first place. They use the examples of the Catarina pupfish and the Christmas Island pipistrelle, a small bat, which have both vanished in recent years.

They argue that the world should be paying attention, because the loss of biological diversity is one of the most severe human-caused global environmental problems.

In the last few decades, humans have taken over vast swathes of animal habitat and caused pollution and global warming. All of which, the authors say, have led to catastrophic declines in populations of both common and rare vertebrate species.

The problem with extinction is that it’s irreversible, and it has a profound effect on the planet’s ecosystem. Everything from the food we eat to the resources that we use are with us because of the Earth’s extraordinary biodiversity.

There’s not enough time, they say, to prevent the shrinking of biodiversity, and any notion that we can somehow bring extinct animals back to life is a “misimpression”.

But not everyone agrees with the scientists’ gloomy assessment.

Earth bouncing back?

Some argue that if we really were in the middle of a mass extinction, the world would already be over. Smithsonian paleontologist Doug Erwin told The Atlantic: “People who claim we’re in the sixth mass extinction don’t understand enough about mass extinctions to understand the logical flaw in their argument.

“To a certain extent they’re claiming it as a way of frightening people into action, when in fact, if it’s actually true we’re in a sixth mass extinction, then there’s no point in conservation biology.”

Although he warns: “I think that if we keep things up long enough, we’ll get to a mass extinction, but we’re not in a mass extinction yet, and I think that’s an optimistic discovery because that means we actually have time to avoid Armageddon.”

And there is another reason for a more optimistic outlook. New species are coming into existence faster than ever thanks to humans, according to Chris D Thomas, Professor of Evolutionary Biology at the University of York.

He argues that we underestimate just how far nature can adapt.

“Throughout the history of the Earth, species have survived by moving to new locations that permit them to flourish,” he says.

“A million or so years from now, the world could end up supporting more species, not fewer, as a consequence of the evolution of Homo sapiens.”

But the authors of the biological annihilation study have a stark warning: even our own days might be numbered.

“Earth’s sixth mass extinction episode has proceeded further than most assume,” they conclude.

“The window for effective action is very short, probably two or three decades at most.

“All signs point to ever more powerful assaults on biodiversity in the next two decades, painting a dismal picture of the future of life, including human life.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

Related topics:

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Future of the EnvironmentSee all

William Austin

April 17, 2024

Victoria Masterson

April 17, 2024

Rebecca Geldard

April 17, 2024

Johnny Wood

April 15, 2024

Johnny Wood

April 15, 2024