It’s not kids’ screen time you should worry about - it’s yours

Many smartphone users exhibit symptoms similar to addiction. Image: REUTERS/Damir Sagolj

Get involved with our crowdsourced digital platform to deliver impact at scale

Stay up to date:

Media, Entertainment and Sport

Much has been written about the dangers of screen time for children.

It’s well known that Bill Gates and Steve Jobs limited their offspring’s use of technology, well placed as they were to see how addictive it can be.

The American Academy of Pediatrics, meanwhile, advises that parents limit screen use to one hour per day for children ages 2 to 5 years, and advises “consistent limits” for children ages 6 and older.

The basic message is that screen time isn’t bad in and of itself, it’s that too much of it can pull a child away from more meaningful activities, such as play, interacting with others and getting a decent night’s sleep.

But what about the parents?

Emerging research is starting to look at the role that parents’ screen usage has on a child’s development, and the news isn’t good.

The lost art of conversation

Early childhood educator and author Erika Christakis writes in The Atlantic that children’s development is being harmed because their parents are constantly distracted by technology.

The average smartphone user checks their phone 85 times a day. Almost half (46%) of Americans say they cannot live without their smartphones.

One of the key charges levelled at distracted parenting is that it harms a young child’s language development, and language is the single best predictor of school achievement.

Christakis references studies showing the importance of conversation for the developing brain.

“The vocal patterns parents everywhere tend to adopt during exchanges with infants and toddlers are marked by a higher-pitched tone, simplified grammar, and engaged, exaggerated enthusiasm. Though this talk is cloying to adult observers, babies can’t get enough of it. Not only that: One study showed that infants exposed to this interactive, emotionally responsive speech style at 11 months and 14 months knew twice as many words at age 2 as ones who weren’t exposed to it,” she writes.

This crucial interaction is in danger of being wiped out, by an incoming text, email or Instagram like.

Lost opportunities

Even if the adult is at pains to teach the child some new words, an incoming communication can render it wasted effort.

In an experiment involving 38 mothers and their two-year-olds, the mothers were asked to teach their toddlers two new words, one at a time. During one of the learning periods, the mother’s phone would ring and she would stop and take the call. In the other, the mother would not be interrupted. Children learned the word when the teaching was not interrupted, but when the interaction was interrupted, they didn’t learn the word.

Christakis also argues that children are programmed to get their caregivers attention, meaning that the constantly distracted parent is unwittingly likely to increase the bad behaviour and tantrums that youngsters often rely on to get attention.

Increased danger

Perhaps more alarmingly, Christakis also points out that distracted parents put their children in danger.

Another study that Christakis references found that visits to hospital for children under five increased in areas of the city that received 3G.

From 2005 to 2012, injuries to children under five increased by 10% as the network of 3G was expanded. The authors of the study suggest that the reason is that smartphones distract caregivers from supervising children.

The addicted parent

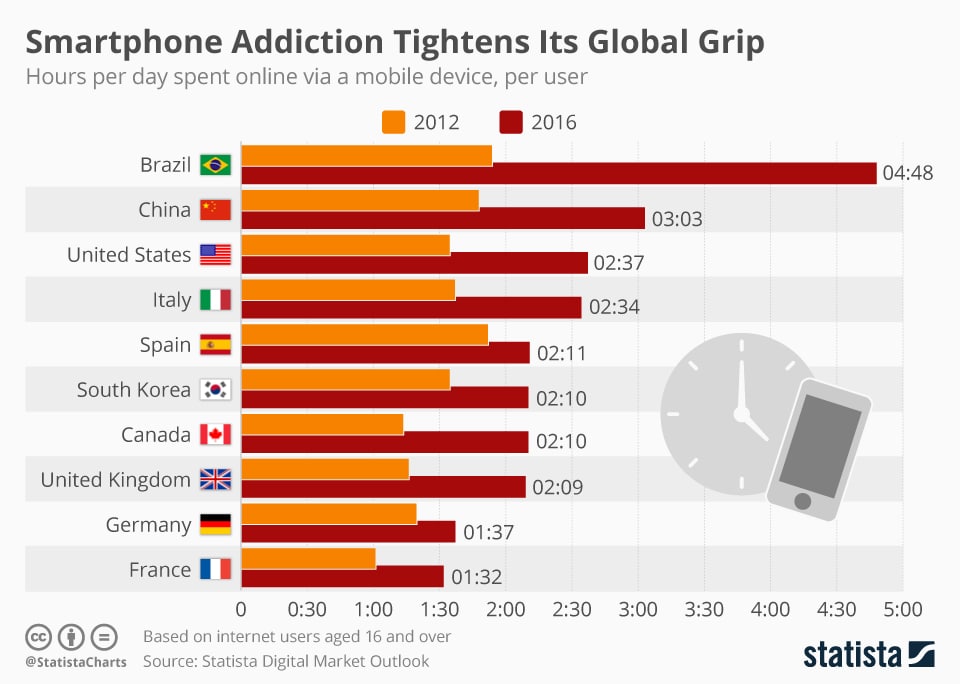

Many users of smartphones exhibit symptoms of addiction, such as constantly feeling the need to check their phone, getting angry if they can’t, or doing it even if it is inappropriate or dangerous for them to do so.

So, not only are interactions between caregiver and child constantly interrupted, the parent can also be grumpier.

“A tuned-out parent may be quicker to anger than an engaged one,” cautions Christakis.

But Christakis isn’t extolling the virtues of helicopter parenting, far from it. Telling a child to entertain themselves while the parent completes chores, or to go out and play are perfectly valid, she argues. Children need to learn independence, but the issue is that parents are present, yet not present.

“We seem to have stumbled into the worst model of parenting imaginable - always present physically, thereby blocking children’s autonomy, yet only fitfully present emotionally.

It doesn’t do adults much good either, she adds, likening always being on to being “stuck in the digital equivalent of the spin cycle.”

“Parents should give themselves permission to back off from the suffocating pressure to be all things to all people. Put your kid in a playpen, already! Ditch that soccer-game appearance if you feel like it. Your kid will be fine. But when you are with your child, put down your damned phone.”

Don't miss any update on this topic

Create a free account and access your personalized content collection with our latest publications and analyses.

License and Republishing

World Economic Forum articles may be republished in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International Public License, and in accordance with our Terms of Use.

The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone and not the World Economic Forum.

The Agenda Weekly

A weekly update of the most important issues driving the global agenda

You can unsubscribe at any time using the link in our emails. For more details, review our privacy policy.

More on Media, Entertainment and SportSee all

Victoria Masterson

April 5, 2024

Jesus Serrano

March 7, 2024

John Letzing

March 5, 2024

Spencer Feingold

March 4, 2024